Definition of Bacterial Transformation

Bacterial transformation is the movement of free DNA from donor bacteria into the extracellular environment, resulting in absorption and, in most cases, the expression of the newly acquired characteristic in a recipient bacterium.

- There is no requirement for a live donor cell for this procedure, and just free DNA in the environment is required.

- Transformant is the recipient who effectively spreads the new DNA.

- Bacterial genera exposed to extreme environmental circumstances will spontaneously release DNA into the environment where the competent cells can take it up. Competent cells react to changes in the environment and use a natural transformation process to govern the level of gene uptake.

- The method of gene transfer that is used most frequently is transformation, which is the greatest means to accomplish the transfer of changed DNA into recipient cells.

- The process of transformation can transport DNA sections with lengths ranging from tens of kilobases to tens of megabases.

Principle of Bacterial Transformations

- Bacterial transformation relies on bacteria’s innate capacity to release DNA, that is subsequently picked up by some other competent bacterium.

- The competence of the host cell determines the success of transformation. The ability of a cell to add naked DNA to the process of transformation is called competence.

- Organisms which are naturally capable of adapting automatically release their DNA by autolysis in the late stationary phase.

- Some bacteria, such as E. coli, can be produced in the laboratory in large quantities and then subjected to treatment to enhance their transformability with chemicals like calcium, or exposed to a strong electric field (electroporation) or a heat shock.

- The permeability of the cell wall is increased by electroporation or heat shock, which allows the donor DNA to enter.

- Similarly, if the converted DNA has a selective marker, like antibiotic resistance, or if the DNA encodes for the usage of a growth factor, such as an amino acid, transformants can be selected.

- The free DNA connects to the bacteria in the majority of naturally competent bacteria, and the DNA is integrated into the chromosomal DNA.

- Rarely, free DNA is introduced into a plasmid, but inserts do not have to be integrated into the chromosome if the plasmid can replicate autonomously from the chromosome.

- After transformation, the plasmid expresses several enzymes and antibiotic-resistant indicators that are active in transforming cells.

- To be successful, the DNA should first be incorporated into the plasmid during this process of transformation. After the donor DNA plasmid has been placed in the competent bacterium, the plasmid including the donor DNA is next introduced into the bacteria.

- The bacteria bearing the plasmid can be identified using a growth medium treated with a particular antibiotic following the transformation.

Stages of bacterial transformation

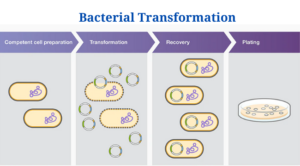

There are four stages in the transformation process:

- The acquisition of competency,

- DNA binding to the cell surface,

- Free DNA processing as well as absorption (typically in a 3′ to 5′ direction), and

- Recombination is the process by which DNA is integrated into a chromosome.

- Electroporation or heat shock treatment can be used to artificially develop competence. The decision is dependent on the effectiveness of the transformation, the goals of the experiment, and the resources available.

- Heat shock is accomplished by keeping the cell-DNA mixture on ice (0°C) and then raising the temperature to 42°C.

- Electroporation begins by exposing the combination to a short, high-voltage pulse in an electroporator.

- Noncovalent binding occurs between double-stranded DNA released from lysed cells and cell surface receptors. In order for these creatures to assimilate DNA from outside their species, there is no DNA sequence-specific recognition; hence, these organisms can potentially carry DNA from beyond their species.

- As soon as the double-stranded DNA has been nicked, it is broken into smaller fragments by endonucleases contained in the cell membrane, and the single-stranded DNA is then translocated across a cell membrane-spanning channel.

- This DNA was modified and now acts as though it were a chromosomal fragment that has been substituted by another chromosomal fragment by the process of recombination. But in order for this integration to work, both the piece donating DNA and the fragment in the chromosome must have a significant nucleotide sequence homology.

- In the case of plasmid, the plasmid with the donor DNA is introduced into the cell when the cell is stressed, such as by exposure to heat shock or electricity. By introducing a specific antibiotic into the growth media, you can spot the cells containing the plasmid.

Figure: Key steps in the process of bacterial transformation: (1) competent cell preparation, (2) transformation of cells, (3) cell recovery, and (4) cell plating. Image Source: Thermo Fisher Scientific

Classification of Bacterial Transformation

(a) Natural transformation

- It is the ability of bacteria naturally to incorporate DNA from the environment into their own genomes without human assistance.

(b) Artificial transformation

- When developing the ability of the host cell to support artificial transformation, various strategies are used.

(c) Bacterial transformation examples

- Bacterial transformation was first and foremost demonstrated by the change of Streptococcus pneumonia’s DNA from smooth-capsule-positive colonies to rough-capsule-negative colonies. The discovery of this new process of bacterial genetic exchange marked the beginning of the scientific understanding of microbes.

- The bacteria that causes neisseria meningitis and H. influenzae uptake DNA from their own species, via species-specific recognition.

- As for B. subtilis, natural bacterial transformation is also observed.

Bacterial Transformation Citations

- McGee, David & Coker, Christopher & Harro, Janette & Mobley, Harry. (2001). Bacterial Genetic Exchange. Doi: 10.1038/npg.els.0001416.

- Griffiths AJF, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, et al. An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. 7th edition. New York: W. H. Freeman; 2000. Bacterial transformation.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21993

Related Posts

- Phylum Porifera: Classification, Characteristics, Examples

- Dissecting Microscope (Stereo Microscope) Definition, Principle, Uses, Parts

- Epithelial Tissue Vs Connective Tissue: Definition, 16+ Differences, Examples

- 29+ Differences Between Arteries and Veins

- 31+ Differences Between DNA and RNA (DNA vs RNA)

- Eukaryotic Cells: Definition, Parts, Structure, Examples

- Centrifugal Force: Definition, Principle, Formula, Examples

- Asexual Vs Sexual Reproduction: Overview, 18+ Differences, Examples

- Glandular Epithelium: Location, Structure, Functions, Examples

- 25+ Differences between Invertebrates and Vertebrates

- Lineweaver–Burk Plot

- Cilia and Flagella: Definition, Structure, Functions and Diagram

- P-value: Definition, Formula, Table and Calculation

- Nucleosome Model of Chromosome

- Northern Blot: Overview, Principle, Procedure and Results