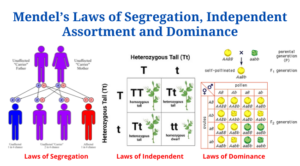

Mendel’s Laws of Segregation, Independent Assortment and Dominance

- This new theory of inheritance was first proposed in the early 1860s by an Austrian monk named Gregor Mendel depending on his experiments with pea plants at the University of Vienna.

- Heredity was Mendel’s belief, and each unit (or gene) in an individual’s genome acted independently of the others.

- Mendelian theory held that the inheritance of a trait was dependent on the transmission of these units.

- As a result of this, an individual possesses a pair of two genes for any trait. Alleles are what we call the various forms of these components now that we comprehend them.

- A person’s homozygosity for a trait is defined as having two identical alleles, while heterozygosity is defined as having two distinct alleles.

- During the mid-1800s, a monk’s breeding experiments lay the foundation for the science of genetics.

- After seven years of research, he published his findings in 1866, which were ignored until 1900 when three different botanists, who were also interested in heredity theories, separately cited the work as being important.

- He was known as the “Father of Genetics” because of his contributions to the field.

- There was a new branch of genetics named after him, called Mendelian genetics, which deals with the study of inheritance of both qualitative and quantitative features, as well as the influence of environment on their expressions, that was named after Mendelian genetics.

- Mendel’s rules, which were first proposed in 1865 and 1866, were rediscover in 1900 and are the basis for Mendelian inheritance.

Experiment carried out by Mendel.

His monastery’s garden was used for breeding studies to determine inheritance patterns. Over numerous generations, he selectively crossbred common pea plants (Pisum sativum) with specified features. For example, he crossed tall and short stems, and discovered that the next generation, the “F1” (first filial generation), was totally made up of individuals expressing only one of the features. There is a 3:1 ratio in children when this generation is interbred. Three individuals have the same trait as one parent and one individual has the other parent’s trait, resulting in a “F2” (second filial generation).

There are several laws that Mendel established.

Image Created with BioRender

1 . Mendel’s First Law of Genetic Segregation

- Alleles are segregated (separated) from one another during meiosis such that each gamete contains only one of the alleles, according to the Law of Segregation.

- As a result, an offspring inherits two alleles for a trait from each of its parents by inheriting homologous chromosomes.

- It follows from this that during meiosis, two members of a gene pair separate from each other; each gamete has an equal chance to inherit one of the genes.

2. Second Law of Mendel’s Law of Independent Assortment

- The second law of Mendel. Gene pairs that are neither related or distantly linked segregate independently, according to the law of independent assortment.

- Alleles for distinct qualities are passed independently, according to the Law of Independent Assortment.

- A trait-specific allele’s biochemical selection is unrelated to the selection of an allele for any other characteristic.

- During his dihybrid cross studies, Mendel found evidence for this law. A 3:1 ratio of dominant and recessive phenotypes was achieved in his monohybrid crosses. A 9:3:3:1 ratio was observed in dihybrid crossings.

- A 3:1 phenotypic ratio for each of the two alleles shows that they are independent.

3. Mendel’s Third Law of Dominance

- Each individual has a unique genotype, which is made up of all the alleles it has.

- Phenotypic characteristics of individuals are determined by their alleles as well as their environment.

- There is no guarantee that an allele will manifest itself in the individual who possesses it.

- It’s called heterozygosity when one of two inherited genes (the dominant allele) has a detectable effect on an organism’s appearance, whereas another gene (the recessive allele) has no discernible effect.

- As a result, the recessive allele’s phenotypic consequences will be hidden by the dominant allele.

- However, it is not a transmission law: it is concerned with the expression of a genotype’s traits.

- It is common for uppercase letters to denote dominant alleles, although the use of lowercase letters is more common.

Mendel’s Laws Citations

- Gardner, E. J., Simmons, M. J., & Snustad, D. P. (1991). Principles of genetics. New York: J. Wiley.

- https://www.cliffsnotes.com/study-guides/biology/plant-biology/genetics/mendelian-genetics

- http://kmbiology.weebly.com/mendel-and-genetics—notes.html

- http://knowgenetics.org/mendelian-genetics/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mendelian_inheritance

Related Posts

- Phylum Porifera: Classification, Characteristics, Examples

- Dissecting Microscope (Stereo Microscope) Definition, Principle, Uses, Parts

- Epithelial Tissue Vs Connective Tissue: Definition, 16+ Differences, Examples

- 29+ Differences Between Arteries and Veins

- 31+ Differences Between DNA and RNA (DNA vs RNA)

- Eukaryotic Cells: Definition, Parts, Structure, Examples

- Centrifugal Force: Definition, Principle, Formula, Examples

- Asexual Vs Sexual Reproduction: Overview, 18+ Differences, Examples

- Glandular Epithelium: Location, Structure, Functions, Examples

- 25+ Differences between Invertebrates and Vertebrates

- Lineweaver–Burk Plot

- Cilia and Flagella: Definition, Structure, Functions and Diagram

- P-value: Definition, Formula, Table and Calculation

- Nucleosome Model of Chromosome

- Northern Blot: Overview, Principle, Procedure and Results